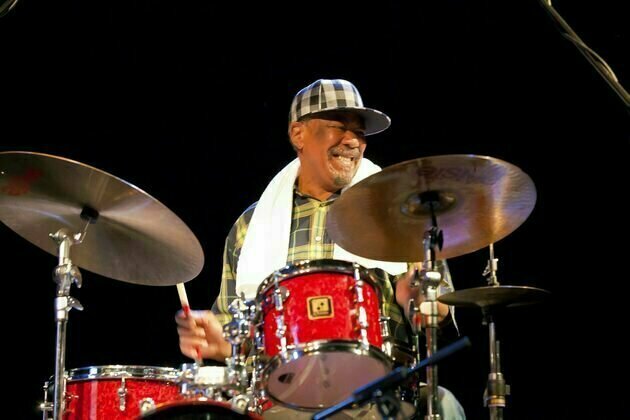

Louis Moholo-Moholo, a lion of South African jazz who used his drums to find freedom

The Conversation

19 Jun 2025, 15:14 GMT+10

Louis Tebugo Moholo-Moholo was born in St Monica's Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa on 10 March 1940. He'd not have appreciated that introduction, once chastising an interviewer:

Ah, no! My name is this; I was born by the river? You want me to start like that? You want me to do all that stuff?

In fact, asked by another journalist to reflect on where he came from

he immediately slid into the power salute of the anti-apartheid movement.

Those two responses sum up the drum master who died on 13 June 2025: a self-effacing but defiantly straight talker with a deep grasp of the politics of the music work - playing, composing, teaching - he devoted his life to.

But for the sake of the record we need to do some of that stuff. Like most South African families, his had travelled: first from neighbouring Lesotho to the diamond fields of the Free State province and then, as in his father's case, from there to Cape Town in search of better employment.

His family wasn't musical (though he recalls his father occasionally playing piano) but enjoyed music. His father would tune in to broadcasts for the then-British naval base at Simonstown, where the young Louis "liked what I heard - Ted Heath, Big Sid Catlett - and later found out it was jazz".

He was drawn to rhythm from an early age, excited by the beats he could create by banging the family sink with sticks or rattling his ruler along a fence on the way home from school. Watching the Scouts marching band, he recalled:

It used to fascinate me the way the cat on the big bass drum used to swing that thing and play boom-boom-boom. I would play on top of a tin can just imitating...

Eventually he was admitted to the Mother City Junior Scouts Band, playing the kettle drums.

But they got taken away because the scoutmaster said I was playing too much. I was unruly - but I had tasted the real thing and now I couldn't leave it!

"Self-taught" - the term many obituaries have used - had a particular meaning in apartheid South Africa, where Black learners were barred from formal music schooling. Moholo-Moholo tried visiting the University of Cape Town to find out about music classes

but the guy (at the gate) wouldn't even let me get into the premises.

So "self-taught" for musicians under apartheid actually meant being schooled by senior musicians within the community. There he observed people playing traditional and more modern popular music, like kwela and mbaqanga and began to learn from experience.

The first band he joined was the Young Rhythm Chordettes and he gigged around Cape Town with many other musicians. Veteran drummer Phaks Joya was his first jazz rhythm mentor.

Moholo (who double-barreled his surname later) came to national consciousness after joining tenor saxophonist Ronnie Beer's group the Swinging City Six. At the 1962 Johannesburg Cold Castle Festival, the 22-year-old Moholo tied for drum first prize with Early Mabuza, already reckoned the top jazz drummer in the country.

Read more: Remembering the Blue Notes: South Africa's first generation of free jazz

Preparing for the festival solidified his relationship with pianist Chris McGregor. Moholo was arrested and sent to jail under South Africa's infamous pass laws. McGregor found out and helped get him released. They got into McGregor's car and headed straight for rehearsal.

That typifies how apartheid was stifling movement and creativity. As a South African jazz researcher I have often focussed on this period. Racially mixed groups could not be on the same stage (Moholo-Moholo often had to play behind a curtain). Being caught without a pass (ID document) after dark meant jail. Under states of emergency, gatherings of more than four people (including rehearsals) could be counted conspiracies - and playing for political gatherings definitely were. His kit was smashed up more than once by the police.

Like many of his contemporaries, Moholo-Moholo broke all the rules regularly. As a result he was in and out of jail. At one point he was handed over to a potato farmer to serve his sentence through indentured labour. ("I was sold, man! Can you believe it? Sold!")

McGregor, a white South African, could sometimes evade restrictions when playing in black residential areas called townships by putting polish on his face and pulling his cap right down. But that trick couldn't work the other way round when they needed to play in white areas.

Read more: What lost photos of Blue Notes say about South Africa's jazz history

And that's why, when Moholo-Moholo and McGregor co-founded one of South Africa's most famous jazz bands ever, the Blue Notes, they chose that name. It wasn't simply an allusion to cultural ties across the Atlantic. They were blue. They played all the notes.

Apartheid left Moholo-Moholo with a righteous, lifelong fury against injustice, but not bitterness. He always saw beyond race.

The next part of the drummer's story - the band's invitation to a French music festival and the extended, often precarious sojourn of its members in Europe - is well documented.

Two aspects drew Moholo-Moholo to the improvised jazz and free music scene in Europe. The first was that it chimed with African heritage music:

We don't count 1-2-3-4-5 and then play. You just pick up your horn or whatever and then you blow. And everyone else just chips in.

But the second was the politics:

I just wanted to be free, totally free, even in music ... It's just so beautiful. 'Let my people go!' ... It's a cry from the inside; no inhibitions...

Moholo-Moholo's South African passport was withdrawn because of his anti-apartheid activities. Exile overseas wasn't easy. He famously observed:

If I could be born again and know I'm going to come to be in exile, then no way (would I take up music), because exile is a fucker.

The South Africans worked intensely hard, but still met racism. The commercialisation of the western music scene depressed him. He had to play to pay the rent, rather than to play free.

It's impossible to fully map Moholo-Moholo's distinguished European career. There are close to 100 recordings, as leader, collaborator and sideman. He led and worked in jazz groups including McGregor's Brotherhood of Breath and founded Viva La Black. There were the short-lived Afro-rock project Assagai and too many collaborations with big name jazz artists to list here.

Moholo-Moholo was acknowledged universally as a pioneer and lion of the international free jazz scene. His early drum heroes and mentors, Sid Catlett from the US and Phaks Joya, were both players with a big, domineering sound. (When drummers do a loud "ooh-yah, ooh-yah" closing flourish, it's Catlett they're echoing.) Moholo-Moholo took from them that potential for muscular, powerhouse volume.

But while he could - and did - use it, he was also capable of delicate, intricate fretworks, subtle pulses, gentle conversations with other, quieter instruments. He was a drummer who listened intently to what his comrades on the stand were doing, and offered what they needed as well as what he must say.

Through it all, he missed home. When he returned to South Africa from London in 2005 (at first for a festival) he was overjoyed by the defeat of apartheid, saddened that the rest of his Blue Notes family hadn't lived to make it back with him, and optimistic about the future.

The South African jazz community welcomed him gladly and respectfully, and there were joyous creative collaborations like Born To Be Black. There were festival headline appearances, retrospectives and honours - including an honorary doctorate from the university whose gate guard had chased him away those many years ago, and national orders. Although local audiences loved him, he was still offered many more overseas gigs and his towering international stature grew.

And as he grew older, emotionally wounded by the death of his beloved wife Mpumie, and physically weakened by a near-death encounter with Covid, travelling and working (and thus earning) became increasingly exhausting. Official words were rarely accompanied by any practical interest in the day-to-day circumstances of his survival.

But I don't believe Louis Moholo-Moholo would want his story to end on that note. He chose to live his life in freedom and resistance because:

There was a war on and we couldn't let them win.

Celebrate that life and its magnificent creativity, because he'd probably tell South Africans we still can't taste true freedom.

A version of this article first appeared on the author's blog

Share

Share

Tweet

Tweet

Share

Share

Flip

Flip

Email

Email

Watch latest videos

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Johannesburg Life news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Johannesburg Life.

More InformationInternational

SectionNew banquet rules in China after deaths, part of Xi’s crackdown

BEIJING, China: Chinese civil servants are now facing stricter rules on dining together, with some local authorities limiting group...

Tehran seeks ceasefire via Gulf allies, offers nuclear flexibility

DUBAI, U.A.E.: As violence escalates between Iran and Israel, Tehran is turning to its Gulf neighbors to help broker a ceasefire —...

Blaise Metreweli becomes first woman to head MI6

LONDON, U.K.: On June 15, Britain named Blaise Metreweli as the first woman to lead the Secret Intelligence Service, commonly known...

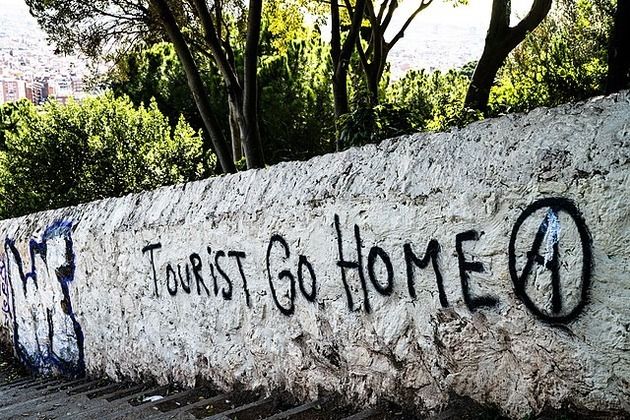

'Tourists go home': Anti-over-tourism protests erupt in Barcelona

BARCELONA/MADRID, Spain: With another record-breaking tourist season underway, thousands of residents across southern Europe marched...

Flight recorder may reveal cause of deadly crash of Air India Boeing

NEW DELHI, India: The flight data recorder from the crashed Air India plane was found on June 13. This vital discovery may help investigators...

Severe storm strikes Dongfang in Southern China

BEIJING, China: A typhoon altered its course and struck Hainan Island, southern China, late on the night of June 13. Typhoon Wutip...

Africa

SectionUNAIDS: Trump’s HIV aid cuts risk reversing global progress

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa: A key global plan to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 is now in deeper jeopardy after the United...

"Exciting time for Indian cricket to be under new leadership": Ben Stokes after Shubman Gill's appointment as Test skipper

Leeds [UK], June 19 (ANI): Ahead of the first Test against India, England skipper Ben Stokes said that the visitors have an 'exciting...

Int'l Exchange | Medical school in Changsha promotes TCM, fosters global ties with African students

CHANGSHA, June 19 (Xinhua) -- The international exchanges division of Changsha Medical University was established in 2006. Currently,...

Indian cricket has 'enormous' pool of talent: Ben Stokes on 'young' India squad for England series

Leeds [UK], June 19 (ANI): England Test skipper Ben Stokes heaped praise on the Indian youngsters in the squad and called the current...

Crudely choked: Why must this nation struggle to refine its own oil?

The Dangote Refinery, accounting for over a quarter of all refining capacity in Africa, is set to solve problems with the struggling...

Crudely choked: Why must this nation struggle to refine its own oil

The Dangote Refinery, accounting for over a quarter of all refining capacity in Africa, is set to solve problems with the struggling...